Boston Globe: Cambridge startup Pickle Robot seeks to automate the dreary work of unloading trucks

Green Machine

By Hiawatha Bray

January 3, 2025

The Boston Globe

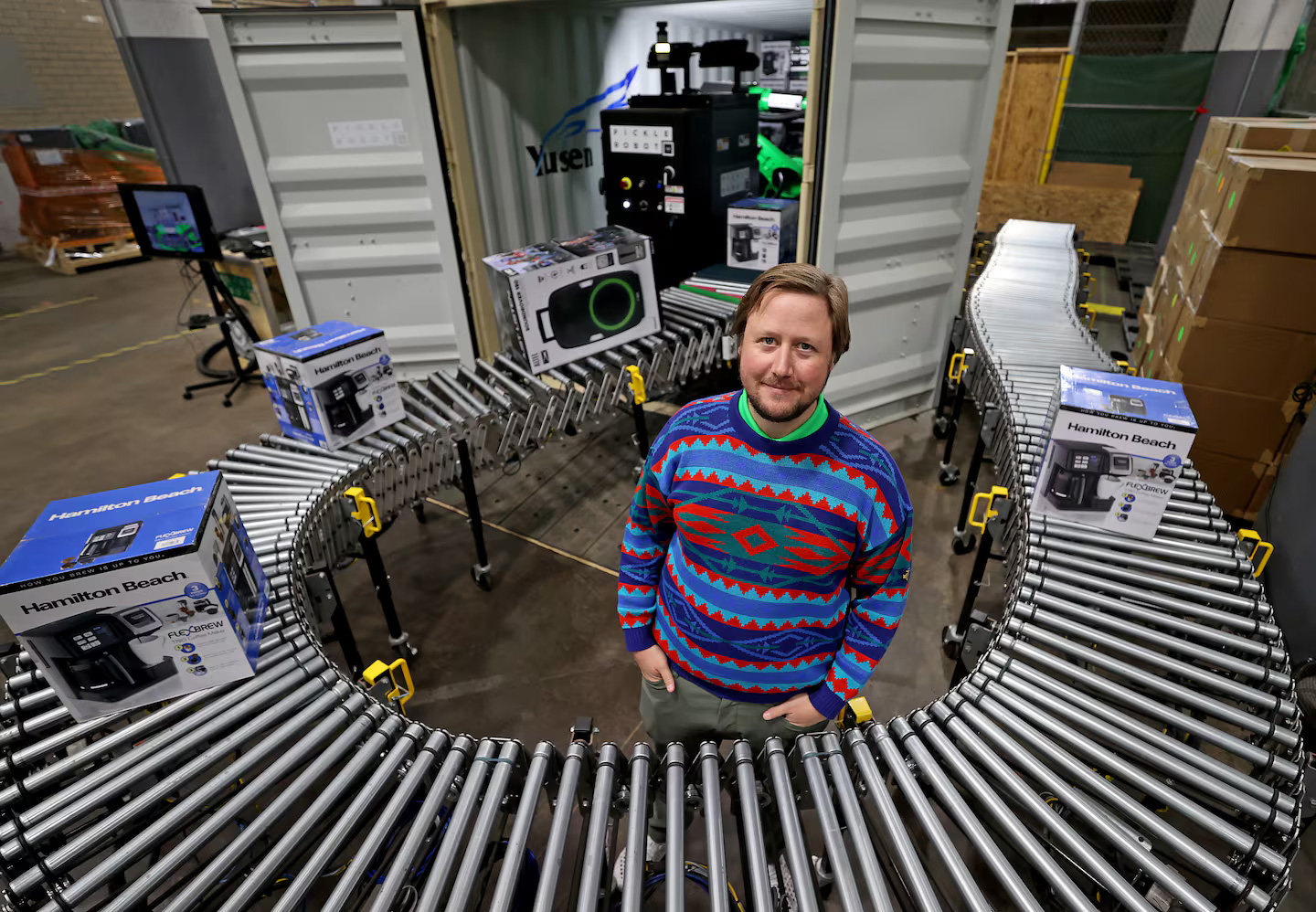

DAVID L. RYAN/GLOBE STAFF

A test site for Pickle Robot, which makes robots that unload trucks, in Charlestown.

The gifts that were heaped under millions of Christmas trees last week didn’t come off a sleigh. Virtually all of them were unloaded from a truck, by legions of tired, often-grumpy humans.

And many of these humans soon could be doing something else. Anyway, that’s the plan at Pickle Robot Co. in Cambridge, a firm founded by people who believe machines — not humans or elves — should unload trucks.

The company’s massive robot, mounted on motorized wheels and sporting a huge mechanical arm, uses a air-suction gripper to lift boxes, which are plopped onto a conveyor belt. Guided by artificial intelligence software, the robot inches deeper into the trailer, clearing out the boxes layer by layer. One human at a remote workstation can control five or six robots at a time.

“Pickles” are already on duty at a handful of commercial warehouses, which lease the machines for $70,000 per robot per year.

Pickle’s competitors include local rival Boston Dynamics and its Stretch robot, a highly mobile battery-powered machine that unloads trucks and can also be programmed to work on other tasks, like stacking boxes onto shipping pallets.

But Pickle is laser-focused on working inside trucks. “The market is unbelievably huge,” said company cofounder Andrew Meyer, who estimates that warehouses worldwide spend $100 billion per year paying people to load and unload trucks. Pickle can make its fortune with just a sliver of that market, and Meyer predicts the company can capture a lot more than a sliver.

DAVID L. RYAN/GLOBE STAFF

Andrew Meyer, an electrical engineer trained at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, launched Pickle Robot in 2018 along with two other MIT alums.

“The biggest warehouses might have the need for 200 to 400, just around the dock doors,” he said. When Pickle introduces a version that can load boxes onto shipping pallets for delivery to retail stores, Mayer thinks a single large warehouse could keep a thousand Pickles busy.

Meyer, an electrical engineer trained at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, launched Pickle in 2018 along with fellow MIT alums Ariana Eisenstein and Dan Paluska. The three wanted to launch a company that would apply artificial intelligence to robotics, but weren’t sure which market to tackle.

“We started with the question, what’s a good problem?” said Meyer. “And man, the first time I saw somebody load a truck in the wintertime, all the light bulbs went off.

But why the curious name? It’s a no-brainer, said Meyer. “It’s a robot that picks up boxes.”

Get it? Pick-le.

Besides, added vice president of marketing Peter Blair, it sounds non-threatening, almost friendly. “It’s really tough to go home and tell your husband or wife ... ’oh, I’m afraid of the Pickle robot,’” Blair said.

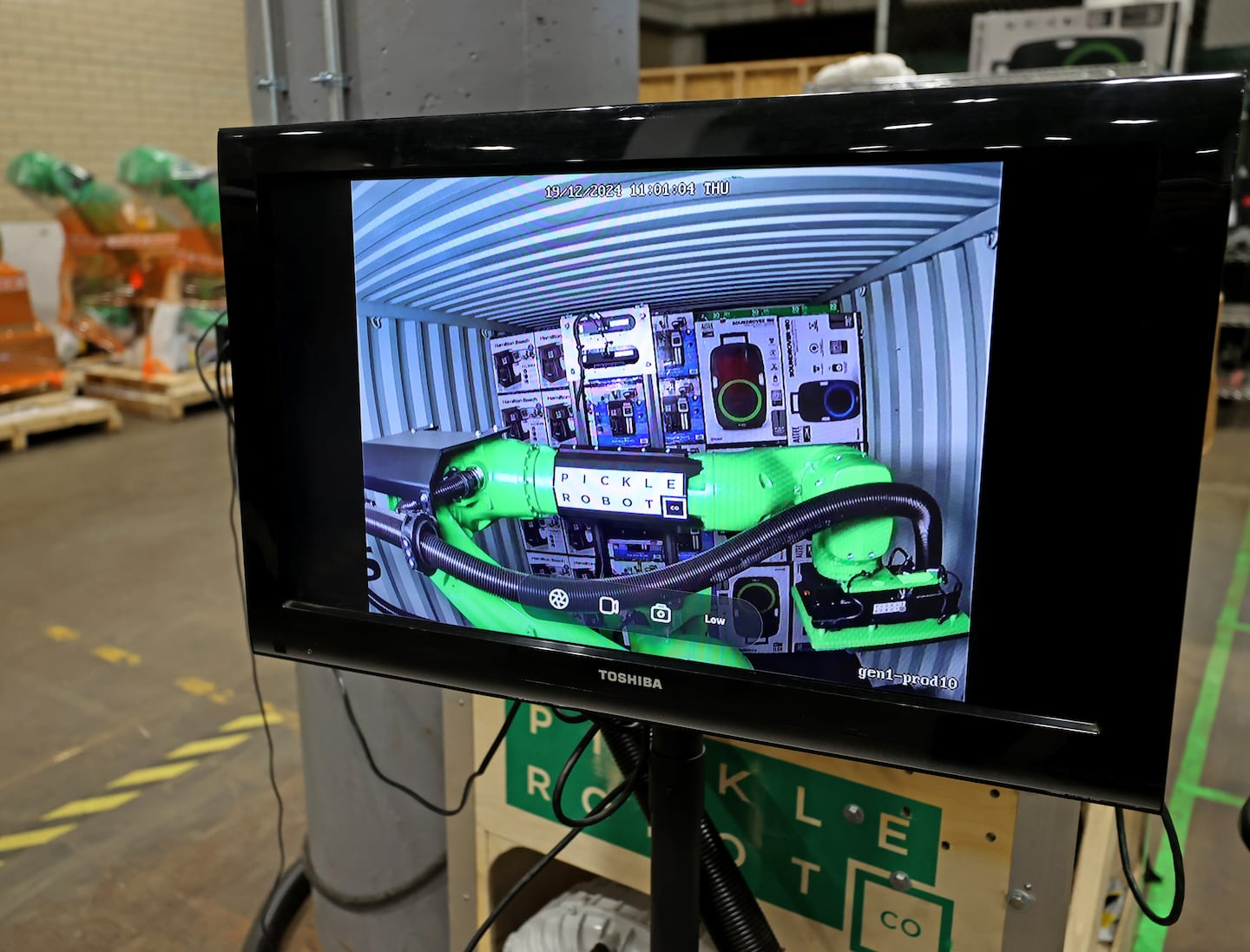

Pickle’s engineers mainly develop the software that makes the machine go. It uses images from multiple video cameras to look at stacked boxes, then applies artificial intelligence to figure out the best way to lift the box and place it onto a conveyor. The robot learns as it goes, deciding which box to pick next, based on the size and weight of remaining boxes. For smaller or lighter items, it can even lift two boxes at once.

DAVID L. RYAN/GLOBE STAFF

A screen used for testing a robot at Pickle Robot in Charlestown.

Pickle fabricates the hefty steel frame that supports the robot, but just about every other component is purchased off the shelf, including the $30,000 robotic arm made by Kuka of Germany, and a powerful vacuum motor that sounds like an aircraft engine. This motor provides suction for the robot’s pneumatic pickup, capable of lifting boxes weighing up to 60 pounds.

The Pickle is designed to be safe despite its massive size. Its undercarriage is studded with LIDAR sensors that use lasers to detect nearby objects. Meyer said the robot can come to a complete halt in less than a second, and it will, if it detects a human within reach.

For now, Pickle is used exclusively to unload trucks. Dropping boxes onto a conveyor belt is relatively easy. But loading a truck will require AI algorithms smart enough to figure out optimum weight distribution and the most efficient use of space. Getting that part right will take some time, said Meyer, but Pickle is working on it.

Adhish Luitel, principal analyst in supply chain management at ABI Research, thinks Pickle needs to hurry up. Luitel says that rival firms, including the Japanese company Mujin, are ahead in developing systems that can both load and unload trucks.

“I do think it’s a problem for them,” said Luitel. “Load and unload, they’re both needed.”

But Blair said that Pickle isn’t losing any sales to Mujin. “We are well ahead in our complexity capabilities for unload and will catch up quick on load,” he said.

Besides, automated unloading is an attractive proposition for some companies. TTI/Ryobi, a Chinese-owned power tool company with operations in Anderson, S.C., has installed two Pickle robots and have four more on order. “It’s working real well,” said Scott Johnson, the company’s senior vice president for distribution. “These guys seem to have figured it out.”

DAVID L. RYAN/GLOBE STAFF

A view at Pickle Robot in Charlestown, a maker of truck-unloading robots.

Privacy Policy

Terms of Use

Copyright © 2025 Pickle Robot Company. All rights reserved.